Art by Elizabeth Keiser

Women in Refrigerators

Batgirl had a great life in comics until she became a symbol of vengeance for Commissioner Gordon and Batman and became known as a woman in a refrigerator. The term women in refrigerators refers to the “disproportionate number of superheroines who have been either depowered, raped, or cut up and stuck in the refrigerator” as discussed in Suzanne Scott’s article “Fangirls in Refrigerators: The Politics of (In)visibility in Comic Book Culture.”

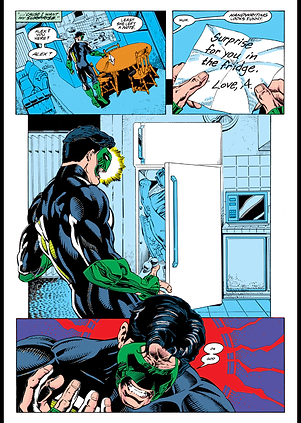

To clarify, the trope gets it’s name from Green Lantern #54 where Green Lantern Kyle Rayner comes home to find his girlfriend Alexandra DeWitt cut into pieces and left in his refrigerator for him to find. Motivated by anger and grief, he pursues and battles her killer, the villan known as Major Force. The term “women in refrigerators” was coined by Gail Simone, a well-renowned female comic book writer to call this lazy and neglectful writing technique out. The term is shorthand for a long standing tradition in the storytelling history of patriarchal societies, where women are either the motivation for or the goal of a man’s journey. These stories roll off to the younger generations that read them, and intentional or not, inform them of how their society is to be structured.

It works that way with all stories. For instance, if in every movie children watch, the person who thinks nothing of killing innocent civilians is painted as the bad guy, what children will come to the conclusion that not valuing human life is part of what makes you bad. In the same vein, what message are we giving to children if there’s a common narrative that shows women are most valuable when they are ultimately either prizes or motivational tools for men?

Following the Green Lantern incident, Simone and her colleagues developed a list of other fictional female characters who had been “killed, maimed, or depowered”, particularly when women are just a device to move the male character’s story arc forward, instead of a fully developed character in her own right. Where do young girls turn when they want representations of their own superheroes, say one that they can hold in their own hands as surrogates of their own stories as powerful, motivated characters?

Batgirl herself becomes a victim of the women in refrigerators trope. Going back to The Killing Joke (as shown in the clip above), Barbara is spending time with her father, Commissioner Gordon. Joker rings the doorbell and when Barbara answers, he shoots her point blank in the spine. While she lays bleeding on the floor, his men take a distraught Commissioner Gordon away while the Joker undresses her and takes nude pictures of her broken body before leaving her to die. When Barbara wakes up in the hospital, she learns that she will not walk for the rest of her life. This serves as motivation for both Batman and her father in their physical and mental battle with the Joker, advancing their stories while Barbara simply lays in the hospital recuperating. The book ends with Batman and Joker sharing a joke and an eerie laugh. There’s no mention of Batgirl or her condition and what that will mean for the character. The recent animated adaptation written by Brian Azzarello tries to rectify Batgirl’s lack of agency and fails spectularly: the addition of her attraction to Batman, the random and out of character consummation of these feelings, the awkward attempt at reconciliation and Batman taking her incapacitation more personally than her father who was the real target of the attack. The movie would show her becoming Oracle, but this continuation of her role as a crime fighter does not have as much weight in the plot as it would in the comics.

Some have made the argument that women in refrigerators also happens to male characters, but in “Women in Refrigerators: Killing Females in Comics”, Aaron Hatch explains:

The counter-argument made against WiR (Women in Refrigerators) is that it symbolizes how women are victims in real life, and the writers are just commentating on this issue in their stories. True, we do live in a day and age where a lot of women have become victims to despicable men, and it is important to reflect ongoing issues in day to day life. However, the problem with this argument is that most stories involving WiR do not really have anything profound to say about female violence. The stories’ themes are not really centered around female violence, and female characters are killed (or maimed) simply to invoke shock into the reader.

The following year, Batgirl came back as the master hacker and scourge of the underworld, Oracle, continuing to help Batman in his quest against crime and becoming a cultural icon for the disabled. Even from the confines of a wheelchair, she continued to appeal to readers worldwide. In Supergirls by Mike Madrid, she’s described as “a mysterious, faceless entity that could invade anyone’s world through her sophisticated computer network, representing the cold technological place the world was becoming. She was ruthless, manipulative, ever vigilant, and terrifying, much like Batman.”

In 1996, DC decided on an experiment known as the Birds of Prey in which a down-on-her-luck Black Canary receives a call from the mysterious information broker Oracle. Oracle offers her an all-expenses paid assignment (Canary had just split from Green Arrow who died shortly after) with a new costume. The book focuses on Oracle and the Black Canary and gradually adds other members in future storylines. But when it’s just the two, Black Canary acts as Batgirl’s second body, allowing her to move again, even if only through vicarious means.

They develop a genuine friendship over the course of the book as Gail Simone took the book over in 2003, creating an all-female superhero team. Rounding out the team was Lady Blackhawk and Huntress, with Oracle at the head, pulling in other cast-offs from the superheroine community. But Oracle, formerly Batgirl, discovers her true purpose: “I’m Oracle. I help people who have no one. People in need.”

Oracle was a great symbol of the disabled and in 2011, she was given the use of her legs back when Gail Simone revived Batgirl in the New 52 reboot of DC Comics. Fans were disappointed that Oracle’s tenure would essentially be erased, but they were excited she was getting her own title finally. But fans realized that the Joker had had an impact on Barbara: she had developed Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder because of the events of The Killing Joke.

Both Batgirl and Jessica Jones deal with their PTSD differently: Batgirl fights crime through others like Batman and the Birds of Prey whereas Jessica Jones tries to run or drink the pain away until she realizes that Kilgrave, the man responsible for her pain, is back and it’s up to her to stop him. However, it does not make either character better than the other. It instead shows that there are different ways of coping with PTSD. We need more compassion in the world and both women manifest that compassion differently.

Batgirl is a study in how to recover from a traumatic event, even if it’s not being shot and being disabled for twenty years. Her story arc is about how to recover from other events: cancer, loved ones dying, and rape, among other things. Batgirl teaches us to persevere, to give back in spite of our trauma, and above all, not to lose hope.